Postludes to Conquest: Bison and Imperialism in Anglo-American Discourse After the Civil War

By Jack Chelgren

From its inception, US imperialism has been complexly bound up with animals, both domesticated and wild. Virginia DeJohn Anderson makes the compelling case in Creatures of Empire (2004) that the role of domestic animals has been underemphasized in accounts of how Europeans and their descendants came to dominate the continent. Animal husbandry was not only a part of the colonists’ agenda of civilizing Native Americans, but moreover “a pretext for conquest” (6-7). In some cases animals were even active vehicles of colonization, causing property damage and disputes among settlers and First Nations. When First Nations failed to adopt an agrarian lifestyle to the white newcomers’ liking, colonists saw it as their prerogative to displace and subjugate them—a prerogative that doubled as necessity when population growth and experiments in free-range husbandry required more land for development.

Anderson’s argument applies to American imperialism and westward expansion as well: the supplanting of the American bison by domesticated cattle stands as perhaps the most extreme example in American history of the deliberate manipulation of animals to facilitate a political conquest. The same basic demands for constant economic, political, and territorial acquisition that Anderson identifies in colonial New England gave impetus to the destruction of the bison and resulting displacement of midwestern First Nations in the years following the Civil War. Therefore, the precipitous and coincident declines of these two groups must not be seen as accidental or unrelated. To the contrary, the erasure of traditional Native lifeways in the final decades of the nineteenth century and the simultaneous near-annihilation of the bison were mutually enforcing, deliberate, and purposeful consequences of the same political agenda. The drastic reduction of the plains bison population, though ostensibly carried out in a decentralized manner by various actors, was as necessary for the development of the American beef industry, and therein American empire, as was the subjugation of Indians for the fulfillment of the imperialist program. In fact, the former conquest represents a microcosm of and a crucial stage in the latter.

This essay examines how depictions of bison in a sampling of postbellum Anglo-American discursive artifacts (paintings, photographs, and literature) frame dominant conceptions of the western landscape and the Native Americans who inhabited it, as well as American national identity. By the end of the nineteenth century, westward expansion was slowing. Indeed, in 1893, Frederick Jackson Turner declared that the frontier, previously the defining force of American imperialism, had closed (Turner 2007). A necessary corollary of Turner’s conclusion is that, with the closing of the frontier, Native Americans had already been conquered, subjected to forced assimilation programs, and relocated to reservations. Bison populations, too, had already been reduced to a fraction of their midcentury numbers. But because showing this reality candidly might have called into question the righteousness of the nation and its purported destiny, depictions of bison and First Nations in the final decades of the century are largely retrospective and idealized, representing both groups with an almost mythical nostalgia. By depicting the pre-conquest frontier as uninhabited and undomesticated; the colonists who moved west as noble, even divinely chosen; and the nations inhabiting that space as amoral and naïve, depictions of bison after the Civil War affirm the established imperial order, legitimizing Anglo-American hegemony.

Throughout the nineteenth century, the frontier grew in both material and mythical-ideological significance to Anglo-American culture, imagined as a repository of unclaimed space and other resources. Agricultural development of the Upper Mississippi Valley and the Great Plains took off in the late 1860s and early 1870s, spurred on by the completion of the first transcontinental railroads, which made accessing the purportedly wide-open spaces of the west easier than ever before. Especially in more central and western prairie regions, however, the dry climate proved more conducive to raising livestock than crops. Consequently, the Great Plains became a major site of cattle raising, especially once railroads connected the herds of the south-central states to the burgeoning stockyards in Chicago. In the 1860s, ’70s, and ’80s, entrepreneurial ranchers rounded up herds of wandering Texas longhorns and drove them to hubs like Abilene, Kansas, for rail shipment north (Cronon 2001). The arrival of the Union Pacific and Kansas Pacific railroads in the American heartland facilitated the connection of western, central, and southwestern beef to a national and even international market. However, the explosive growth of the industry and its unprecedented demand for livestock required the systematic and rapid removal of the bison, whose herds had up to that point numbered the tens of millions (ibid.). By rendering the Great Plains more accessible, the railroads gave rise to a sharp uptick in the practice of hunting bison for their fur and hides—a trend only compounded when a Philadelphia tannery pioneered new techniques of processing buffalo hides into leather in 1870 (ibid., Carlson 2001).

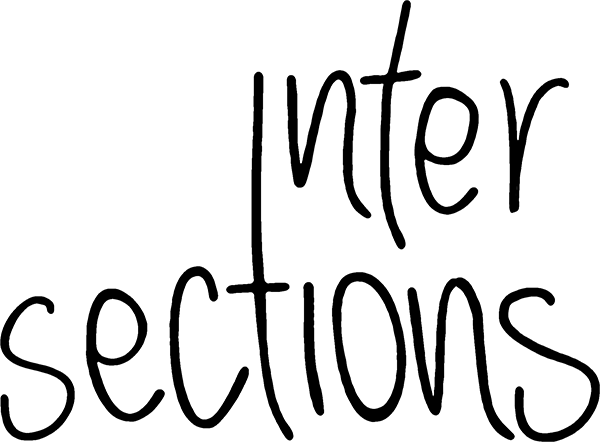

Hunting bison for sport grew rapidly popular; poachers would fire at bison out of the windows of passing trains, and frequently would not even stop to collect their spoils. A wood engraving titled “The far west.—Shooting buffalo on the line of the Kansas-Pacific Railroad,” printed in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in June of 1871, sensationally captures the wanton slaughter in which these locomotive-borne hunters indulged (fig. 1). The depiction is polemical, tacitly condemning the shooters through the hyperbolic mayhem of the scene: a dozen bison leaping off the tracks in front of the train, with scores more falling over themselves, head-butting each other, and collapsing in death on either side. But, conceivably, the critique could run still deeper. The composition of the engraving echoes several famous nineteenth century representations of trains, Joseph Mallord William Turner’s Rain, Steam, Speed (1844) and Andrew Melrose’s Westward the Star of Empire Takes Its Way—near Council Bluffs, Iowa (1867) (fig. 2). Both paintings frame the advance of a locomotive as an emblem of technological innovation, and Melrose’s title explicitly defines it as an agent of righteous imperialism. By echoing these precedents while presenting the train as a force of destruction and cruelty, the engraving may imply a powerful skepticism regarding expansionist notions of progress. Certainly, “the far west” is not a space of prosperity or ennoblement here, but one of gratuitous violence and excess.

Indeed, the toll that hunting for leather and sport took on the bison gave new meaning to gratuity. From 1870 to 1874, more than four million bison were slaughtered in the Midwest (Carlson 105). The nexus of the killing shifted to Texas in the four years that followed as hunters pursued the dwindling herds southward, but it was not long until there were simply too few bison to hunt (Cronon 2001). A haunting photograph of a man standing atop an enormous pile of bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer hints at the incomprehensible scale of the extermination (fig. 3). The image renders unavoidable the fact that, regardless of the use or waste to which the animals were committed, their destruction was ultimately a demonstration of American power. Certainly, there were economic motivations: the bison were part of a plains ecosystem incompatible with the cattle industry that American imperialism valorized and demanded. But the image is furthermore suggestive of the degree to which the extension of American empire in the nineteenth century epitomizes Achille Mbembe’s concept—reworking Foucauldian biopower—of “necropolitics,” which holds that “the ultimate expression of sovereignty resides … in the power and the capacity to dictate who may live and who must die” (Mbembe 2003, 11). The extermination of the bison exemplifies the deployment of death to exert political control, as the direct perpetration of animal slaughter—carried out diffusely but rapidly, and facilitated by state-sponsored infrastructure (the railroads)—cemented the subjugation of the Plains Indian nations. Anglo-American industry essentially waged undeclared economic and ecological warfare against the First Nations it encountered, destroying or appropriating the bison they depended on until the Indians’ old ways of life were irretrievable.

Americans justified their westward expansion, and more specifically their biocultural siege on Native Americans and bison, from several ideological directions, all of which may be united under the umbrella of Manifest Destiny. The term has been frequently used and frequently debated; for the purposes of this essay, a few lines from John O’Sullivan, published in 1839 in The United States Democratic Review, will suffice to develop a preliminary definition:

so far as regards the entire development of the natural rights of man, in moral, political, and national life, we may confidently assume that our country is destined to be the great nation of futurity … The expansive future is our arena, and for our history. We are entering on its untrodden space, with the truths of God in our minds, beneficent objects in our hearts, and with a clear conscience unsullied by the past (426-27, original emphasis).

O’Sullivan would coin the term “Manifest Destiny” itself several years later, but the ideology is already in place here. It consists, fundamentally, in the conviction that the United States represented the highest form of nationhood and political life; that it was Americans’ divinely ordained, benevolent duty to extend their culture and sphere of influence; and finally—implicitly in the above, but not elsewhere—that the western North American continent was a domain of opportunity, of literal “untrodden space” and untapped resources, that made it an ideal stage for expanding the nation. Though O’Sullivan does not openly reference westward migration in the passage above, his eliding of geography, history, and futurity signals that his vision of the nation’s destiny requires nothing less than the continuation of the progress already made—a progress west across the continent. Just a few lines later, he renders his vision more explicit: the “floor” of American greatness, he writes, “shall be a hemisphere” (427).

In a peculiar and skillful discursive ploy, Anglo-American representations of the west often show First Nations in their historical environments while simultaneously advancing the implication that these spaces were not really occupied—that they were, at the very least, being under-utilized, and were therefore available for the taking. Such a half-erasure of Native presence figures prominently in the vast landscape paintings of the American luminist tradition, and particularly the Hudson River School, which present massive and dazzling wilderness spaces, often suffused with imperialist invitations to the presumed white, western viewer. Albert Bierstadt’s The Rocky Mountains: Lander’s Peak (1863) is paradigmatic (fig. 4). The spectator looks, unnoticed, over a Shoshone encampment, which is rendered in the same warm earth tones as the landscape around it (Roque 1987). The viewing angle positions one slightly above the Native Americans, who blend in with their surroundings, and thus present no obstacle to one’s masterful, unchallenged gaze. Soaring mountain peaks covered in snow and wreathed in clouds rise above the miniscule humans in the foreground, rendering them inoffensive and innocuous. It is a scene at once dazzling and tranquil, promising the viewer ennobling adventure and sublime transcendence. The message is unambiguous: this is unoccupied space, ready for the taking.

No major nineteenth century source on Manifest Destiny goes quite so far as to name the removal of bison as a necessary precondition for American empire. But the suggestion is pervasive that civilizational progress involved the domination of the landscape and the beings that inhabited it. Cronon (2001) quotes an anonymous English visitor to the Great Plains in the 1860s as predicting: “Nothing short of violence or special legislation can prevent the plains from continuing to be forever that which under nature’s farming they have ever been—the feeding ground for mighty flocks, the cattle pasture of the world” (quoted on 214). The Englishman writes as if the displacement of bison were already complete, foregrounding the irony that both violence and legislation were in fact underway to realize the very “cattle pasture” he envisioned. An 1873 promotional photograph produced by the Kansas Pacific Railway shows five men posing with several dozen taxidermied bison heads outside the company’s main office in Kansas City (fig. 5). A small sign at the bottom left reads “Go West! Go West! Go to Kansas – Colorado! Free Homes!” The image is tremendously revealing. It confirms, first, that the eradication of the bison—and with it, the conversion of the plains into cattle grazing territory—was still underway in the early 1870s; the English tourist’s declaration must therefore be understood as either simply mistaken or, more insidiously, performing an imperialist optimism by framing the replacement of the bison by domesticated cattle as a natural and inevitable fact. But the railway photograph illustrates still other, broader ideological operations. In it, the bison heads become trophies of, and therein a synecdoche for, the power and opportunity associated with moving west. The image specifically plays on anxieties surrounding economic solvency and masculinity, insinuating through the examples of these sturdy-looking, serious men and the promise of “Free Homes!” that relocating west was all one needed to do to secure a life of independence and rugged strength expressed through dominion over the animal world.

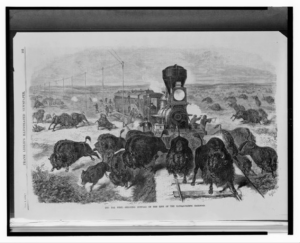

The relationship between American imperialism, bison hunting, and constructions of white masculinity may seem far-fetched. But one need only consider how western discourses of expansion and progress are invariably framed as the holy duty of white men—who were, of course, always the main political actors in Anglo-American society—to discern how fundamental that ideological triangulation truly is. It was conventional, certainly, to refer as O’Sullivan does to humankind as “man,” and to view white men as the ablest, most advanced, and most natural leaders of that category. But the common sense status of white men as the default human subject only affirms the degree to which white supremacist patriarchy suffused dominant discourse. Another photograph from 1873, this one a studio portrait of a Colorado hunting party posing with a pair of bison heads, displays as frankly as one could imagine a group of white men defining their masculinity and power through the subjugation of bison (fig. 6). Coupled with the men’s defiant, swaggering postures, the X-shaped arrangement of the composition—founded, significantly, literally on top of the animals’ heads—gives spatial form to the domination that was the apotheosis and endgame of Manifest Destiny.

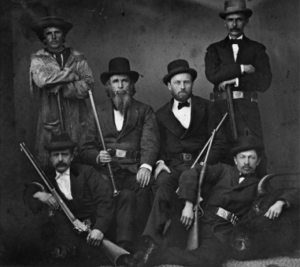

Deeply embedded in American imperialism was a sense of religious chosenness and divine justification. Etienne Balibar (1990) and Anthony D. Smith (1999) have noted that national identity is frequently grounded in a sense of the nation as an inevitable, divinely ordained entity. Both scholars further identify a strain of ethnic chosenness in conceptions of nationhood, a trend Smith identifies first in the Israelites of the Old Testament and the Hebrew Bible. And indeed, in the view of many in late nineteenth century America, the task and privilege to push the frontier, to carry forward the national destiny and bring civilization to the tribes and the land they found, was inflected by both religious fatalism and ethnic supremacism. Just as Bierstadt’s The Rocky Mountains: Lander’s Peak exemplifies the construction of an “empty west,” John Gast’s American Progress (1872) is perhaps the quintessential image of the “civilizing” aspect of Manifest Destiny (fig. 7). The piece shows Columbia, an allegory of Anglo-American empire, leading a march of carriage-borne pioneers, explorers, trains, domestic agriculture across the picture plane. Behind them, in the distance, one sees the imminence of thriving, commercial urbanism. At the viewer’s left, the onslaught pushes a generalized mob of Native Americans, dogs, a bear, and bison off the canvas into stormy uncertainty. Another, subtler representative of the same ideology is Asher B. Durand’s similarly titled Progress (1853) (fig. 8). There, Native Americans peer out of a rugged, unmanicured landscape along a coastline that becomes increasingly urbanized as it recedes to a vanishing point—spatializing the ideology of inevitable imperial progress that many Americans imagined and sought to realize.

The Durand painting provides a helpful antebellum foil for the Gast. Considered in apposition, the two works suggest an intensification of imperialist sentiments from before the Civil War to after. The presence of the allegorical goddess in the Gast piece, coupled with the almost cartoonish modeling, indicates a didactic, even propagandistic intention. Rather than depicting a concrete historical moment, both works distill an imperialist fantasy into a single visual composite—the Gast is simply more blunt in its symbolism. One explanation for the more pointed approach could be that, in the aftermath of the Civil War, there was stronger ambient pressure to define a unified national identity. By glorifying westward expansion with a divine personification, and furthermore identifying Native Americans and nondomesticated animals like bison as outsiders to that progress, the painting assigned both racialized and religious significance to the imperialist project, making it a shared purpose of ethnic and cultural improvement around which the divided country could rally.

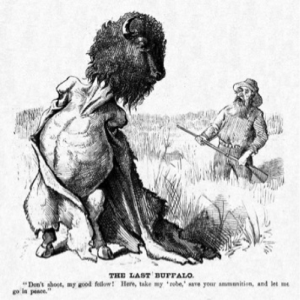

What the Gast sacrifices in artistic refinement, then, it makes up for in the lucidity with which it displays US imperialist ideology. The presence of the herd of bison at the left, on the side of the doomed Native Americans, indicates that at least some Americans were aware not only of First Nations’ dependence on these animals, but also of the fact that the destruction of the one would wreak havoc on the other. Though allegorical, then, and although it portrays its subject as a glorious triumph rather than a trans-species genocide, the image is striking in its fidelity to historical truth. Native Americans and bison were displaced westward—deliberately and relatedly—until they had no place left to go. A bizarre and disturbing cartoon by Thomas Nast called “The Last Buffalo,” emphasizes the same theme with a disturbing note of black humor (fig. 9). Published in the June 6, 1874 edition of Harper’s Weekly, it shows a bipedal, anthropomorphized bison shedding its hide like a coat and surrendering it to an astonished hunter. The caption reads: “Don’t Shoot, My Good Fellow! Here, take my ‘robe’, save your ammunition, and let me go in peace.” Though the animal displays no iconography associating it with Native Americans, its personification inevitably evokes the parallel defeat of those societies, still underway at the time. One of the fundamental tasks of Ulysses S. Grant’s first term in office (1869-1872) was establishing a “peace policy” with Native Americans—a misleadingly titled task at which his administration ultimately failed (Sim 2008). The issue thus loomed prominently in the nation’s attention at the time Harper’s published Nast’s cartoon—and given the consciousness apparent in Gast’s painting of Native Americans’ dependence on the waning bison, the resonance of Native Americans’ fate with the bison shedding its skin in defeat would have been strong.

The conquest of the bison thus marked a discursive and material confirmation of the conquest of the Great Plains First Nations. Some, like the men in the hunting party photograph, celebrated this victory without hesitation. Still others, however, indulged in what the anthropologist James Clifford termed the “salvage paradigm” (quoted in Noble 2006, 184) and which others (Rosaldo 1989) have termed “imperialist nostalgia”: romanticizing a landscape inhabited by bison and Native Americans while nonetheless framing the Anglo-American conquest and the displacement of bison by cattle as an inevitable eventuality. Another, later painting by Bierstadt, The Last of the Buffalo (1888), exemplifies the trend (fig. 10). Like The Rocky Mountains: Lander’s Peak, this work situates the viewer in the position of a white colonist, viewing its halcyon world with the same wistful detachment with which one might contemplate an episode from a myth. Bierstadt completed the piece in 1888, after the original culture, fauna, and topography of the region had been supplanted. By that point, there were hardly any bison left, hence the elegiac tone of the title. Those that remained were primarily hunted by white people. The warm tones, dynamic postures, and dramatic subject matter of the painting thus represent a marked nostalgia—indeed, a conqueror’s imperialist nostalgia for an eradicated world preserved only in the past and the imagination. However much Bierstadt idealizes the Native American warrior and the bison, he affords them power and dignity only in retrospection, as tragic casualties of the necessary progress of history—in contrast to a present-tense power that could threaten the established political order.

There is no accident here: central to the salvage paradigm are the combined relegation of “salvaged” entities to historical obsolescence and affirmation of the dominant historical narrative as the only trajectory events could have taken. The skulls and heaps of slain bison in the foreground present an unmistakable eco-cultural memento mori, foreshadowing the purportedly unavoidable decline of the bison—and with them, by symbolic association, the First Nations whose livelihood was predicated on hunting them. Anglo-European influence creeps into the scene via the striking white horse that the central hunter is riding, revealing that colonization abetted by domesticated animals is well underway even as the bison and the Native hunters remain. Echoing Anderson’s argument in Creatures of Empire, the painting thus allegorizes how the eradication of the plains bison precipitated the domination of the Native American nations who lived there.

Though this paper has focused primarily on images, it was by no means in pictures alone that the discourses of Manifest Destiny operated in the period following the Civil War. Even in the work of so progressive a writer as Walt Whitman, one finds portrayals of both bison and First Nations aligned with imperialist, racially supremacist ideology. In the long poem “Song of Myself” from Leaves of Grass, first published in 1855 but revised and re-released until the poet’s death in 1892, Whitman draws on the Rousseauist noble savage topos, portraying Native Americans as naïve and amoral. “The friendly and flowing savage, who is he?” begins Section 39. “Is he waiting for civilization, or past it and mastering it? / … / Behavior lawless as snow-flakes, words simple as grass, / uncomb’d head, laughter, and naivetè [sic], / Slow-stepping feet, common features, common modes and emanations …” (Whitman, §39). Though Whitman allows that the “savage” he observes here may be superior to and beyond western definitions of civilized life, the repeated emphasis on his “simple,” “slow,” and “common” features is decidedly patronizing. And significantly, the same romanticized simplicity characterizes the sole mention of bison in the poem:

Where the bull advances to do his masculine work, where the stud to the mare, where the cock is treading the hen,

Where the heifers browse, where geese nip their food with short jerks,

Where sun-down shadows lengthen over the limitless and lonesome prairie,

Where herds of buffalo make a crawling spread of the square miles far and near

…

I tread day and night such roads (ibid., §32).

In the context of these lines, it becomes clear that Whitman’s portrayal of the Native American in Section 39 is distinctly animalizing: the animals, like the “savage,” are slow and ruminating, inhabiting the landscape with no awareness of purportedly civilized human concerns.[1]

What makes the portrayal especially problematic is the fact that Whitman, while evincing an awareness of and even reinforcing the imperialist discourses and policies leading to the othering and oppression of Native Americans, does not critique them. In his rural wandering and contemplation of these scenes, the speaker either neglects to identify that bison and cattle do not belong in the same catalog—the one is an undomesticated member of a nearly extinct ecology; the latter is an addition to that ecosystem deployed by Anglo-American newcomers to supplant the former. And on top of that, while lumping the colonized animal and the colonizer indiscriminately together, the poem hints at the eradication of the bison by prefacing its mention of the animal with a strategically placed image of twilight. This image and its connotations of doom pass unchallenged, foreshadowing the destruction of the bison without acknowledging the mechanisms of interspecies oppression and domination behind it.

While problematic, however, it is also incredibly significant that Whitman unites bison and cattle in the above-mentioned lines from Section 32. As the one animal slipped from the landscape like the poem’s ominous sunset—or rather was systematically purged from it—the other rose to prominence. The Texas longhorn and the American bison were two sides of the same ecological coin—inhabiting the same niche, they could not thrive alongside one another, but only in mutually exclusive opposition. But another, rather more literal coin must be mentioned to fully understand what took place in the Great Plains in the final decades of the nineteenth century. It is perhaps the most innocuous and most illustrative token of imperialist nostalgia ever made—the Buffalo Nickel, produced by the United States Mint from 1913 to 1938, and re-released in 2005 (Klinkenborg 2005) (fig. 11). On the face side, the coin shows the head of a Native American in profile; on the obverse, it shows a bison. Perhaps unintentionally, this tiny piece of currency distills and embodies the intertwined fates of the two beings its represents. The First Nations and bison were two sides of the same coin in a different sense, that of being bound together even to their mutual detriment and near destruction. “In the face of that Indian and the somber mass of that bison,” writes Verlyn Klinkenborg in The New York Times, “you can visualize the tragic undertone of American history” (ibid.).

Alongside the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad, the eco-cultural transformation that saw bison and First Nations replaced by cattle and the crescent United States permitted the emergence of Chicago as a major urban industrial center, and the literal muscle behind the American meatpacking industry. Its stockyards became the nexus where the meat of the mid- and southwest was packaged for distribution in the east (Cronon 2001). The city celebrated its ascendency in the 1893 World’s Columbian Exhibition, a World’s Fair commemorating the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s arrival in the Americas. That Chicago aligned its economic triumph with the origins of Anglo-European colonialism was no coincidence. Its agro-industrial complex marked a crowning achievement of Manifest Destiny, as white settlers seized the continent’s territory and resources, reshaped the land, and forced the First Nations into subaltern subjugation.

Appendix

Fig. 1: The far west.—Shooting buffalo on the line of the Kansas-Pacific Railroad, 1871, print of wood engraving, illus. in: Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper 32.818 (1871): 193. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Fig. 2: (Left) Joseph Mallord William Turner, Rain, Steam, Speed, 1844, oil on canvas, 36 in x 48 in, National Gallery, London. (Right) Andrew Melrose, Westward the Star of Empire Takes Its Way—near Council Bluffs, Iowa, 1867, oil on canvas, 25.5 in x 46 in, from the Personal Collection of E. William Judson.

Fig. 3: Men standing with pile of buffalo skulls, Michigan Carbon Works, exact date unknown (late 19th century), photographic print, 7.5 in. x 9.5 in., Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

Fig. 4: Albert Bierstadt, The Rocky Mountains: Lander’s Peak, 1863, oil on canvas, 73.5 in x 120.75 in, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Fig. 5: Robert Benecke, No. 2. Taxidermist’s Department of the Kansas Pacific Railway. Buffalo Heads used for advertising purposes, 1873, photographic print, 19.25 cm x 25 cm, in On the Kansas Pacific Railway. Source: Southern Methodist University Libraries.

Fig. 6: Bartholomew Verlarde, Hunting party, 1873, photographic print, 4 in x 4.5 in, W. N. Byers collection. Source: Denver Public Library Digital Collections.

Fig. 7: John Gast, American Progress, 1872, oil on canvas, 12.75 in x 16.75 in, Museum of the American West, Los Angeles.

Fig. 8: Asher B. Durand, Progress, 1853, oil on canvas, 121.9 cm x 182.8 cm, the Warner Collection of Gulf States Paper Corporation, Tuscaloosa, Alabama.

Fig. 9: Thomas Nast, The Last Buffalo, 1874, illustration in Harper’s Weekly. Source: Isenberg 2000, 146.

Fig. 10: Albert Bierstadt, The Last of the Buffalo, 1888, oil on canvas, 71.3 in x 119.3 in, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Fig. 10: Albert Bierstadt, The Last of the Buffalo, 1888, oil on canvas, 71.3 in x 119.3 in, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Fig. 11: The Buffalo Nickel. Public domain.

Bibliography

Anderson, Virginia DeJohn. Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004.

Balibar, Etienne. “The Nation Form: History and Ideology.” Review 13.3 (1990): 329-61.

Carlson, Laurie Winn. Cattle: An Informal Social History. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001.

Cronon, William. “Annihilating Space: Meat.” In Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West, 207-59. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2001.

Isenberg, Andrew C. The Destruction of the Bison: An Environmental History, 1750-1920. Studies in Environment and History, edited by Donald Worster and J. R. McNeill. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001.

Klinkenborg, Verlyn. “The (Old) Buffalo Nickel.” The New York Times, March 6, 2005.

Mbembe, Achille. “Necropolitics.” Translated by Libby Meintjes. Public Culture 15.1 (2003): 11-40.

Noble, Andrea. “Seeing through ¡Que viva México!: Eisenstein’s Travels in Mexico.” Journal of Iberian and Latin Studies 12.2-3 (2006): 173-87.

O’Sullivan, John. “The Great Nation of Futurity.” The United States Democratic Review 6.23 (1839): 426-30.

Roque, Oswaldo Rodriguez. “The Exaltation of American Landscape Painting.” In American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School, 21-48. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987.

Rosaldo, Renato. “Imperialist Nostalgia.” Representations 26 (1989): 107-22.

Sim, David. “The Peace Policy of Ulysses S. Grant.” American Nineteenth Century History 9.3 (2008): 241-68.

Smith, Anthony D. “Ethnic election and national destiny: some religious origins of nationalist ideals.” Nations and Nationalism 5.3 (1999): 331-55.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” In The Frontier in American History, 1-38. Project Gutenberg eBook, published October 14, 2007. http://www.gutenberg.org/files/22994/22994-h/22994-h.htm.

Whitman, Walt. “Song of Myself.” In Leaves of Grass. Modern American Poetry, Department of English, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/s_z/whitman/song.htm.

[1] Compare the portrayal of animals in the following lines from §32 to that of Native Americans above:

I think I could turn and live with animals, they’re so placid and self-contain’d,

I stand and look at them long and long.

They do not sweat and whine about their condition,

They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins,

They do not make me sick discussing their duty to God,

Not one is dissatisfied, not one is demented with the mania of owning things,

Not one kneels to another, nor to his kind that lived thousands of years ago,

Not one is respectable or unhappy over the whole earth (Whitman).

+ There are no comments

Add yours